2025/12/22

2025/12/22

2023/11/22

Społeczeństwo

2023/11/22

Społeczeństwo

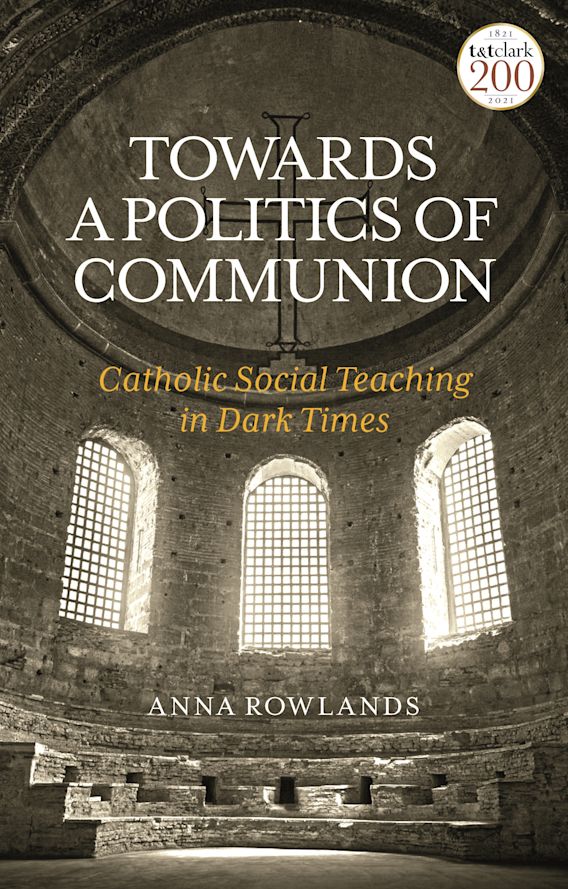

How to see the world in a different way and achieve the desire for a politics closer to the values and fundamental purpose of humanity – Maciej Szepietowski asks prof. Anna Rowlands, author of the book Towards a Politics of Communion. Catholic Social Teaching in Dark Times.

The title of one of your book reviews is „The book on Catholic social teaching that every Catholic should read”. Great recommendation. How did you come up with the idea for the book?

The book began to germinate in my mind at the time of the financial crisis of the early 2000’s. Three factors prompted me to think it was a timely enterprise. Firstly, there seemed to be a general sense that the ethics, worldview and basic anthropologies we had been working with in the West had not served us well in providing stable, equal and just economic systems, and there was a hunger for new resources to help us see the world in a different way. Secondly, I had begun working intensively with migrants who had travelled from the Middle East and Africa into Europe and listening to their stories convinced me that migration ethics was about to become one of the most significant questions of our generation and that we were not well-equipped to deal with this as a profound human reality. Thirdly, both of the previous questions or realities imply a wider failure in our political models, and yet I also sense a degree of frustration at a grassroots level that many people want a politics more attuned to values and deep human purpose. The danger I see is that this desire and the failure of mainstream politics to address this desire can easily lead to its manipulation by those who wish to reinvent politics in a more absolute and less truly dialogical fashion. I fear the consequences of that manipulation. For these reasons, I wished to return to the Catholic social tradition to see what kind of resources it had to offer to speak into this moment. I chose to write a book that laid out the history and development of the key texts and ideas of the tradition but also tried to make connections with our current moment.

The title of the book may suggest that it is pessimistic. Is it so? Are we living in Dark Times?

No, the book is not pessimistic. Nor is it crudely optimistic. It rejects either pessimism or optimism as a helpful paradigm. The title ‘Dark Times’ is a reference to a poem by Berthold Brecht. Brecht wrote ‘To Posterity’ in response to his own agonies about living in an age of struggle, insecurity and challenge, but his focus was on the question of time: how do we live well the time on earth that is given to us? This is the repeated refrain of his poem. Hannah Arendt picks up this refrain in her book ‘Men in Dark Times’ to ask the question of illumination. Who will act as the light that illuminates difficult times? And what kind of lives provide that illumination? Her answer is that these lives are not necessarily those of the cleverest or most representative of the zeitgeist, but rather those who are able to take into themselves the conditions of the age and transform them towards justice and love. She devotes one chapter of her book to Pope John XXIII as an example of such a life. I was inspired in my title by this question of naming the challenges of a time and holding up the traditions that provide pathways to live lives of illumination.

What actually is the common good?

Good question, and the answer you get depends on who you ask! The common good is not originally a Christian idea, rather it has classical origins focused on the public life of the citizen and the city-state. The first Christian writers ‘Christianised’ the idea in important ways, exploring the ways that belief in Christ transformed the horizons of what Christians believed to be truly common and genuinely good. In St Paul’s writings the common good becomes identified with the diverse gifts and charisms of the Body of Christ working together for love and justice. The early Church Fathers tended to focus especially on Matthew 25 as their ‘common good’ text, arguing that the Christian common good was focused on a particular set of embodied practices or habits that focused on the needy and afflicted and their care, what became known later as the works of mercy: feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, welcoming the stranger and migrant, visiting the prisoner etc. The medieval tradition adds a focus on law and the role of the political community in attaining the conditions for the common good. This emphasis on conditions is very important, because it doesn’t imply that you can simply legislate the common good into being. Law provides the conditions to enable virtue, but the achievement of virtue is rather more complex and free a process! This same emphasis on protecting the conditions for justice and virtue translates into the modern papal tradition of reflection on the common good, with the documents of the Second Vatican Council defining the common good as the sum total of the conditions that enable the flourishing of persons and groups. This then requires a wide-ranging public discussion about what those conditions for flourishing are! This is one of the things we are currently struggling with as late modern societies, I would argue! The wider canon of principles of CST try to offer further reflection on those conditions: dignity, solidarity, subsidiarity, preferential option for the poorest and the earth, just distribution of goods intended by the Creator to meet the needs of all.

In the book you reach for various intellectual traditions, you conduct a dialogue with them. So the addressee of the book are also people who do not know the Church and Catholic social teaching?

Yes, exactly. It struck me as very important to write a book that could speak to a deep hunger in society for ways of thinking about neighbour love, rootedness, justice and so forth and that did not assume the reader who was interested in these questions already spoke or thought ‘Catholic’. I wanted to offer the Catholic tradition, in an honest way, as a resource to all ‘people of goodwill’, as the encyclicals note. This tradition of writing for a wider world but out of a Catholic tradition has been key to the self-understanding of the social encyclical tradition since the Second Vatican Council. I believe that the core vision that animates the Catholic social tradition has much to offer to inter-religious engagement, to a secular hunger for a different way of living, as well as to Catholics who often know little of their own social tradition!

You writes about how Catholic social teaching is not just about promoting social justice, but about living as Christians in the world. How to be a witness in the modern world?

Indeed. There is a danger that CST is seen as a specialist subject for those committed to various social justice projects and not as – quite simply – a basic vision for every Christian of how to live well in the world. The basic capacity of a Christian to witness to Christ in the modern world is utterly bound up with questions of human social relationships, the just distribution of material goods, of the capacity to live diversity in unity and the ability to enact and protect the dignity of every human life. Part of the work of the Synod currently underway in the Catholic Church is to increasingly integrate social teaching into the core of our ecclesial lives, and also to renew our ecclesial lives in such a way that we are better fit to proclaim the Gospel to a bleeding world. CST is thoroughly ecclesial, and the Church is a social body, called to proclaim the transformation and salvation of the world in light of the reality of the Kingdom of God.

Thank you.

/mdk